Introduction

This year as I prepared for my RSA talk, Building a Data-Driven Security Strategy, I decided to do something slightly different. I modeled my timing practice after video game speedrunners. Ultimately it was a good experience that I plan to repeat. Here's the story.What is a speedrun?

One thing I do to relax is watch video game speedruns. This is when people try and complete a video game as quickly as possible. (It’s so competitive that on some improvements in records are measured in terms of frames and some players spend months or even years, playing hundreds of thousands of attempts, to try and beat a record.)

One thing they all have in common is they use software to measure how long the attempt (known as a run) takes. Most break the runs down into sections so they can see how well they are doing at various parts of the game. To do this, they use timing software which measure their time per section, and overall time. Additionally, each run is individually stored and their current run is compared to previous runs.

Speedrunning for presenting

This struck me as very similar to what we do for presentations, and so for my presentation, I decided to use a popular timer program, livesplit (specifically livesplit one) to measure how well I did for each practice run of my presentation. Basically, every time I practiced my presentation, I opened the timer program and at each section transition, I clicked it. While the practice run was going, the software would indicate (by color and number) if I was getting close to my comparison time (the average time for that section). Each individual run was then saved in a livesplit xml file (.lss). I’ve attached mine for anyone that wants to play with it here.

|

| Figure 1 |

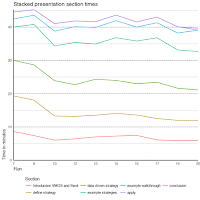

The initial sections analysis (Figure 1) showed some somewhat dirty data. First, there probably shouldn’t be a run -1. Also, runs 4 and 5 look to not be complete. So we’ll limit our analysis to runs 7 to 20. For some reason, The introduction section in runs 9, 14, and 18 seems to be missing, so we’ll eliminate those times as well. It’s worth noting that incomplete runs are common in the speedrunning world and so some runs where no times are saved will be missing and other runs where the practice was cut short will exist as well. It’s also relevant that ‘apply’ and ‘conclusion’ were really mostly the same section and so I normally let ‘apply’s split run until the end of the presentation, making ‘conclusion’ rarely occur at all.

Figure 2 and 3 look much better. A few things that start popping out. First, I did about 20 practice runs though the first several were incomplete. Looking at Figure 2, we see that some sections like ‘introduction VMOS and Swot’, ‘apply’, and ‘data driven strategy’ decrease throughout the practice. On the other hand, ‘example strategies’ and ‘example walkthrough’ increased at the expense of ‘define strategy’. This was due to pulling some example and extra conversation out of the former as feedback I got suggested I should spend more time on the latter. Ultimately it looks like a reduction of about 5 minutes from the first runs to the final presentation on stage (run 20).

The file also provides the overall time for each time. Figure 4 gives a quick look. We can compare it to Figure 3 and see it’s about what we expect. A slight decline from 45 to 40 minutes in runtime between run 7ish to run 20.

|

| Figure 4 |

|

| Figure 5 |

We can also look at actual practice days instead of run numbers. Figure 5 tells an interesting story. I did some rough tests of the talk back in December. This was when I first put the slides together in what would be their final form. Once I had that draft together, I didn’t run it through January and February (as I worked on my part the DBIR). After my DBIR responsibilities started to slow and the RSA slide submission deadline started to come up, I picked back up again. The talk was running a little slow at the beginning of march, however through intermittent practice and refinement I had it down where I wanted it (41-43 minutes) in late March and early April. I had to put off testing it again during the week before and week of the DBIR launch. After DBIR launch I picked it up and practiced it every day while at RSA. It was running a little slow (2 runs over 43 minutes) at the conference, but the last run the morning of was right at 40 minutes with the actual presentation coming in a little faster than I wanted at 39 minutes.

We can take the same look at dates, but by section. Figures 6 and 7 provide the story. It’s not much of a difference, but it does put into perspective the larger changes in the earlier runs as substantially earlier in the development process of the talk.

Conclusion

Ultimately I find this very helpful and suspect others will as well. I regularly get questions such as “how many times do you practice your talk?” or “how long does it take you to create one”. Granted it’s a sample size of 1, but it helps give an idea of how the presentation truly evolved. I can also see how the changes I made as I refined the presentation affected the final presentation. Hopefully a few others will give this a try and post their data to compare!

Wow, this presentation completely nailed the concept of timing! The speaker demonstrated exceptional control and confidence, truly owning the stage like a boss. By the way, if anyone needs assistance with their dissertation, I highly recommend checking out the reliable online dissertation help available online.

ReplyDeleteIt’s interesting how attention to detail can make such a big difference in how a message is received. That same idea applies in online education too when assessments are digital, tools like proctoring software for online exam help ensure tests run fairly and smoothly.

ReplyDelete